1h 45' without intermission

Gyuri, the housband

Áron Dimény

Márta, the wife

Imola Kézdi

Annamari, their daughter

Eszter Román

Grandmother, Gyuri's mother

Andrea Kali

Krisztina, Gyuri's mistress, actress

Csilla Albert

Veress comrade, Krisztina's father

Ervin Szűcs

Lieutenant Balla

Szabolcs Balla

Captain Bajko

András Buzási

Barta, employee of the Department of the Interior

Zsolt Gedő

Lajoska, mover

Attila Orbán

Jánoska, mover

Alpár Fogarasi

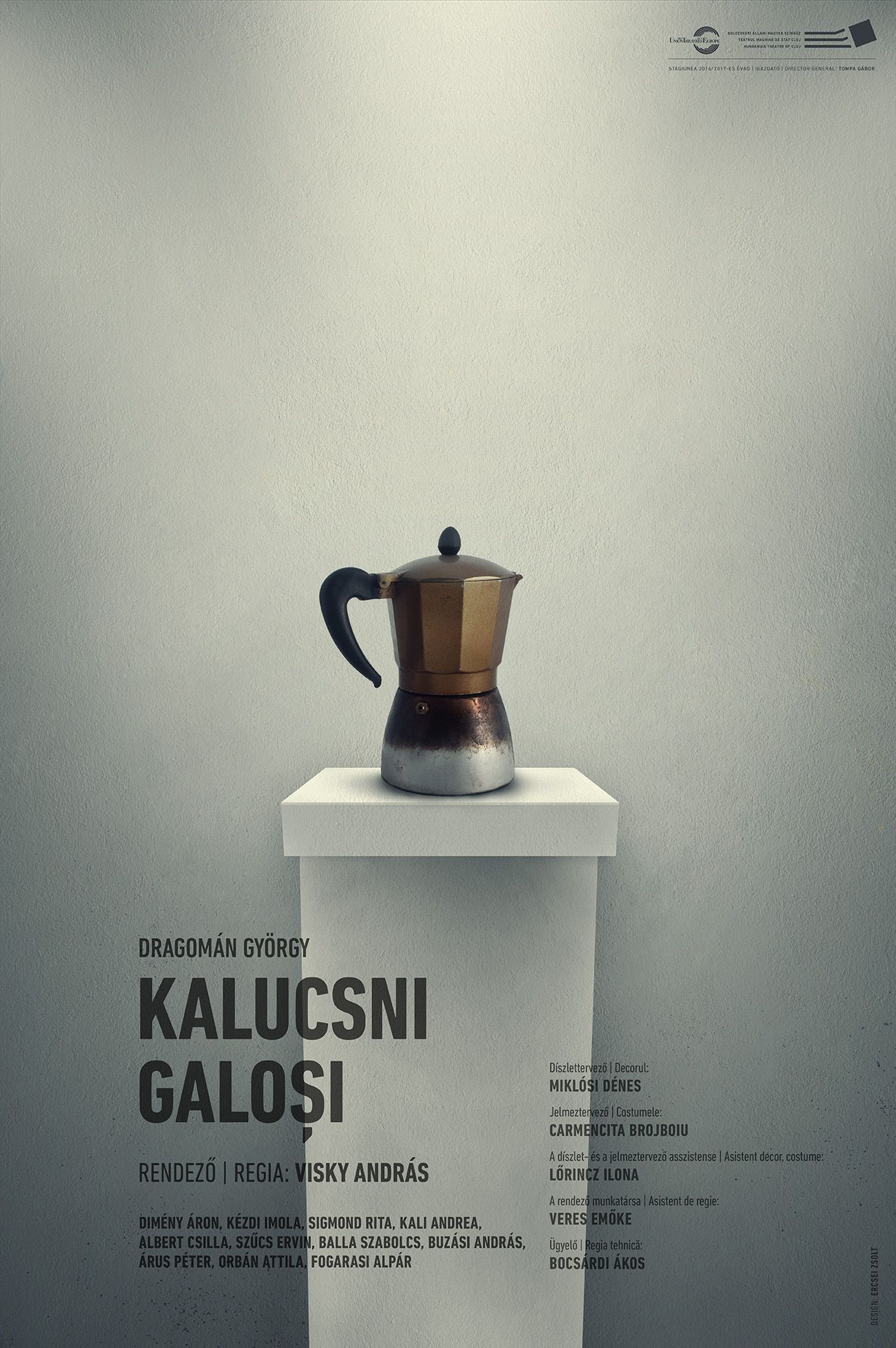

directed by

András Visky

set design

Dénes Miklósi

costume design

Carmencita Brojboiu

set designer`s assistant

Ilona Lőrincz

director's assistant

Emőke Veres

stage manager

Pál Böjthe

I think Galoshes is not only a necessary but also an important production. A performance that speaks to one’s conscience. It is a necessary play because we - who have lived through various stages of the communist dictatorship - also need the therapy of remembrance, especially since some of us - and this is the case much too often - have simply forgotten what and how that was, or some of us are tempted to declare that, after all, things were not so bad in that unfortunate time. People have started to dangerously insinuate that socialism, and the period of the so-called light-years, had also their positive sides. Galoshes is an important production because I find that its staging is also addressed to the young generations who need to find out what it meant to live in the time of great lies and humiliations in the communist age, especially in the current context of the increasingly troubled years in which we now live, a context which is rather confusing and is quite unwilling to negotiate with the aspirations of ordinary people.

The set design (by Dénes Miklósi) and costumes (by Carmencita Brojboiu) of the two-hour long performance that is played without intermission create such a realistic replica of the concrete flat apartment of the 1980s, that even the viewer who had lived in that period is made to gasp in awe, sensing that he is instantly transposed into that time when even the air was stifled. What contributes to this space is that on the wall between the audience and the stage, the Securitate dossiers of well-known public figures are displayed for people to see, read and study - as if in a museum dedicated to communism. Even the play itself is taking place behind a glass, as the viewer sees the space dedicated to the stage as if they were viewing a glass cage, where absurd and tragic events happen within a space furnished to look just like a flat apartment from that era. We experience all the pettiness of this small universe, and then we feel the stifling air of that era, the permanent desire to break out, to escape, which is temporarily compensated by illicit love affairs and the use of luxury goods banned by the communist authorities, however, eventually the ultimate desire to finally escape remains, the goal is still to obtain a passport, for which no price is too great to pay.

For those who lived through the 1980s, the production is breathtakingly lifelike, and for those who were born later, the performance wonderfully illustrates the endless series of impossible situations, the nonsense and vulnerability of which they only know from the stories they have heard. The members of the family of intellectuals, as well as the environment, those who work for and serve the system, all of our fears, our petty desire to dominate and its means to experience that are portrayed in a very realistic way.

It is a play that evokes memories. It conjures up a time, when the only good thing was that we were young. The rest was only doubt, anguish, waiting and the occasional hope that arose. Galoshes is yesterday’s story meant for today and for tomorrow. A memento dedicated to the 1980s. A reminder to notice that things do change, even if they are not always apparent.

The scenes are so intense that one has the impression one is watching a movie, not a stage play. We see before us poignant situations, well-developed characters, even our own lives. The lives that were taken over by power. A power which we fear. The policeman whom we think is allowed to do anything. The politician, the mayor, the building manager, the director, who we believe to be omnipotent. The doctor at the hospital who can be bought. The lawyer, the clerk, who can be bribed. A system, which even though does not exist any longer, the power relations, the patterns of behavior that we inherit from our parents and grandparents inevitably move into this direction, if we are not aware and open enough toward change.

We are also responsible to make sure that the 1980s will not be repeated, and that we will live in a society that is free from corruption and abuse of power. Galoshes holds up a mirror in front of those who are elders and gives courage to the younger ones to dare to act against injustice, the settling in of dictatorial endeavors and models. People like Comrade Veress are among us, but in a different form, for blackmail, humiliation is still an everyday occurrence, and still, we pass them by as if they were natural.

DESZKA Contemporary Hungarian Drama and Theatre Festival, Debrecen, Hungary (2017)

Budapest, Hungary (2017)

Date of the opening: november 16, 2016

Galoshes introduces us into an endogamous and promiscuous small town from Transylvania, in which the lives of the persecutor and of the persecutee, of the member of the secret police, of intellectuals and that of the cunning workers cannot be separated. Everyone is Hungarian, they all share a common language-code, as György Dragomán inserts the play into the myth of Iphigenia: the family pushes a 16 year old girl into the arms of the head of the secret police, in hope of getting emigrant passports. The performance itself is an introduction of sorts into the 1980s, through the life of an intellectual family. By using the tools of cinéma verité, all becomes humanly: the space, the objects, the acting itself. It is about the lives of someone else, which still resonate within us: it is this closeness that might pose an interest even to those who had not been present during the 1980s. They can recognize that they somehow still have the same experiences at school, at home, or at the level of human connection.

András Visky