1h 30' without intermission

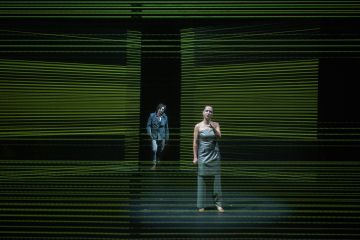

A truly coherent, contemporary and fascinating approach of the theme comes to life - as an entire world in itself - within the Cluj performance, so much so that the viewer gets completely immersed in that world, feeling its great emotional impact. In the studio room the stage area separated by a projection fabric, the impulses, pain, struggle, disappointment wash over the viewers with such might that it touches the audience on a visceral level. Such a result represents the essence of the theatre as such.

As the events unfold, as we get to know the background, the secret that lies behind the events, and all of its repercussions reaching the present tense of the performance, we are thoroughly immersed in the studio space filled indeed with very few tangible objects, the more we get involved in the reality of imaginative and engaging realm of visual elements.

The production seeks to find out what spiritual and mental state does a woman need in order to leave an abusive marriage. Nóra is truly beautiful. She's an attractive woman who takes care of herself. She is stylish, has a cool hairstyle, is fit, and it’s obvious that her appearance is important to her. The perfect object of desire for those like Courier John. Beautiful and empty.

Botond Nagy is the kind of director who has a distinct, easily recognizable theatrical world. There is a mood and even specific technical marks, alongside an audiovisual medium, an attitude that is characteristic for his work. And visual designer András Rancz expands the visual framework of the stage in an amazing way with his projected set.

Here, the reality that our senses have “claimed” is dissolved, and this is necessary when the evidences of patriarchalism have to be eradicated. Because the greatest power is precisely this reality, in which socialization and ultimately our bodies enclose us. The stake taken on by the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj’s production of A Doll’s House is monumental: its deconstruction.

Botond Fischer: Felboncolni a valóságot [Dissecting Reality], helikon.ro, March 25, 2019

I was not mistaken in any way: the hypotheses remained valid, and with Proust's amendment in mind, A Doll’s House directed by Botond Nagy is a production that is full of well carried out surprises, a dramatic piece that is topical, brought into the present time, in which universality as such is amplified. Nora & co lost their traits as the proper bourgeois of the 19th century, and now they adopt the bon chic bon genre style, being the congenial hybrids in which cartoon heroes coexist with excentric characters from Lynch’s cinematic world. Sometimes, in the dollhouse, self-irony is declaimed and self-parody is practiced, approaches which anihilate the duller passages, turning them into short circuits of comical effects. Of course, we are quite aware that that if at least one of the protagonists possessed from the very beginning the self-distancing they mimic, the catastrophe might have been avoided, however, this over the top manifestation that is highlighted is the pure madness that so-called normalcy carries within. Each individual becomes an objectified subconscious that has silenced their convenience and all of the flaws gained through their societal integration.

In productions of Nora, they usually furnish a cosy home in which one might even live lovingly and comfortably. They did this at Vígszínház, or more recently, at the Katona. However, in this fairly poignant production by the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj, set designer Rancz András has opted to restrict even the studio stage. He creates a transparent, perspex nook for the characters, which signifies literally as well as symbolically the restricted space and oppressive atmosphere in which they must dwell.

(…)

Botond Nagy has directed this significant production imaginatively and with striking originality.

Gábor Bóta: A pénz fétise [The fetish of money] – Kisvárda Papers, 23 June 2021

Botond Nagy’s analytic and associative perspective has made it possible for Ibsen’s classic drama dating back almost a century and a half to react to issues still valid today such as women’s equality of rights and independence or existential stability.

Nora’s dilemmas and emotional states are conveyed by something other than the usual realism that places an actual doll’s house on stage. Gone is the idyllic-seeming fantasy of family life; absent are the three children, as well as any set reminiscent of the bourgeois theatre of illusion.

Instead of a text-centred interpretation, it is the emotions and the points of emotional contact between the characters that take precedence.

Szofia Tölli: Dobozba zárt lázadás [Rebellion in a box], 5 August 2021

It is a memorable, slow scene in the show where it is not with the intent of helping her that Nora’s friend approaches the blackmailer, her former lover, who’d sent the check to Helmer, Nora’s husband. The act of Mrs Linde (Albert Csilla) allowing the secret to surface reveals, with a few extra twists, the potential for dispensing justice in (Scandinavian and American) plays of the period, willing, by any cost, to dispel the lie the characters live in. This scene is a beautiful combination of ambivalence in relationships, strengths of character and motivations: betrayal turns into justice being meted out defiantly, yet mainly aimed at winning back her former love, the man. Krostad (Váta Lóránd) extends his hand to her, which the woman may only accept in this fashion: by portraying his advances as being entirely unselfish.

It comes across as foreign, in a good sense, and casts a benevolently sobering light on the period that produced the play, the standards of 150 years ago: it is a demonstration of the crucible out of which feminism is about to coalesce, so that, awakened, Nora wants not to work, but to become even more self-aware, and to leave the doll’s house – but on whose expense? And she would perceive solidarity by her husband to take the rap for her deeds.

Edit V. Gilbert: Önállóan felöltözni [Dressing by oneself], 14 July 2021