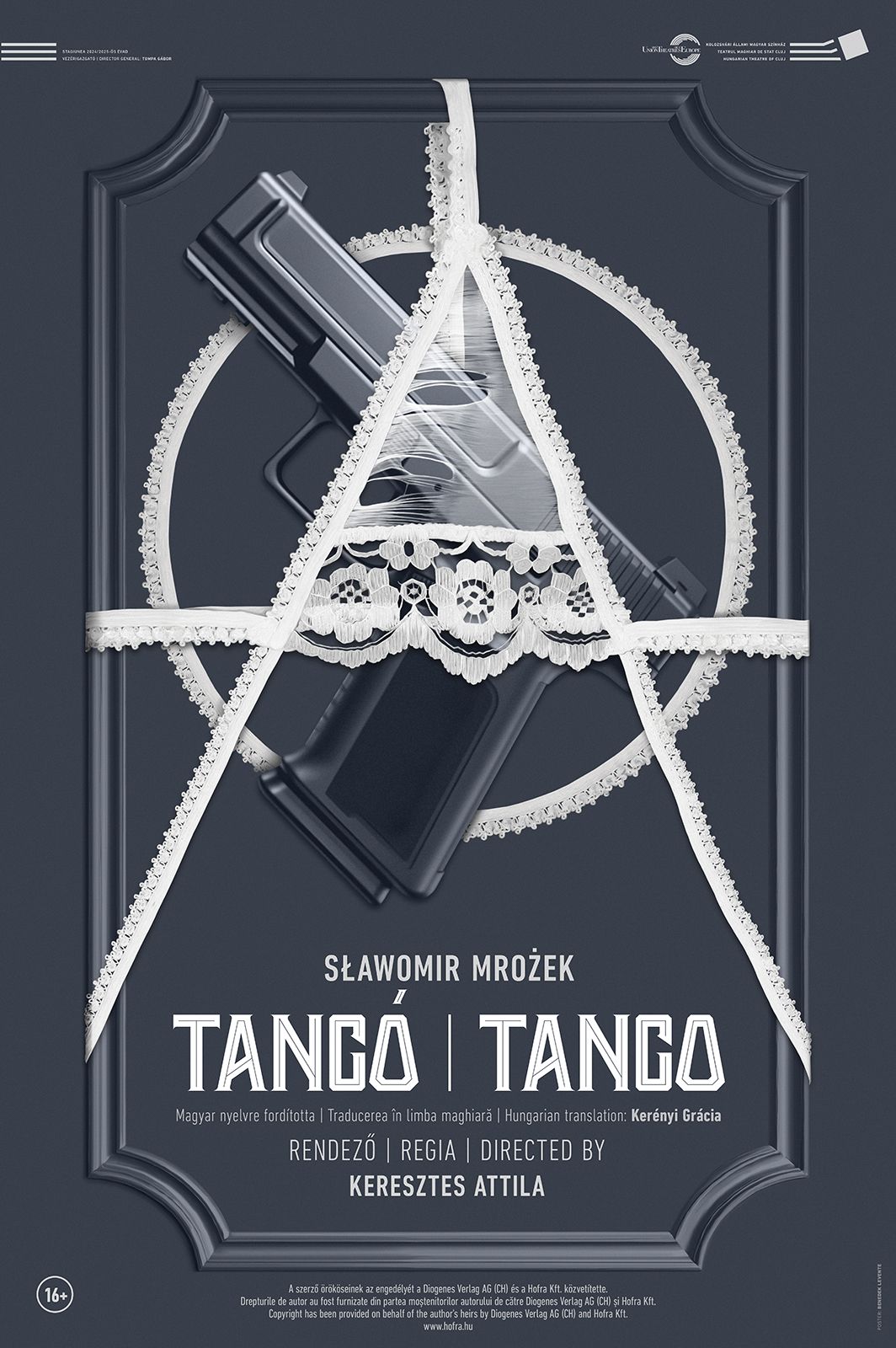

Studio Performance in the Main Hall

2h 45 with intermission

The entire creative team behind the show is perfectly immersed in Mrożek's unsettling universe, abundant with major existential questions. Eugenia's deceptive bohemian lifestyle, complete with violent, youthful whims and episodes of senile apathy, is admirably portrayed by Melinda Kántor. [...] Ervin Szűcs approaches Stomil with a healthy feverishness, without neglecting any of the subtleties of the infantile and perverted nature of Artur's father's illusion of freedom. Attila Orbán accurately renders the petrified docility of the common man, as well as the moral confusion of catastrophic effects caused by the "stratifications of the past," which cause Eleonora's brother to become Artur's accomplice. Emőke Kató proves her ingenuity in traversing Eleonora's different personas, combining sensuality with seriousness and vividly navigating the treacherous polyphony of maternal lucidity, followed by the bouts of frivolity typical of a sybaritic life. With his well-balanced dynamism, Zsolt Gedő exceeds all expectations in his stage performance in Tango, embodying an ambivalent Artur, consumed by contradictions and the anguish of responsibilities that end in nihilism and an animalistic state of intoxication. Zsolt Gedő is particularly convincing when he launches into Artur's declamatory verve and when he experiences the disorientation of double betrayal, that of his father, who is unable to remove the intruder Edek, and that of his adulterous fiancée. In turn, Zsuzsa Tőtszegi brings Ala to life playfully and impetuously, capturing the moral hesitations and fatal arsenal of the eternal feminine. Last but not least, the perfidious and primitive Edek, with his delightful exuberance both in his piano playing and dancing, bears the masterful signature of Lóránd Váta.

Ana Ionesei: Tango sau curajul de a reforma lumea, dansând cu Forma [Tango or the courage to reform the world, dancing with Form], fictiune.ro, No. 208 / 118 (new series) / July 2025

I laughed heartily at the scenes in which the idea asserted its right to exist at the expense of form, just as I appreciated the desire to highlight the importance of power in our daily lives: power seen in its many forms—the power to change things, political power, power as a form of coercion, or power as a manifestation against freedom of thought. Tango is a show of (personal) reflexivity, and I think it is valuable enough that I would like as many young people as possible to see it, but also people who are extremely quick to abandon the values of a democratic system in favor of a totalitarianism that is devastating in every respect.

Nona Rapotan: Toleranța monstruoasă – Sławomir Mrożek pe scena Teatrului Maghiar de Stat Cluj [Monstrous Tolerance – Sławomir Mrożek on stage of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj], bookhub.ro, July 2, 2025

Gedő Zsolt portrays a true character of the eternal rebel. From his first appearance on stage, with a thunderous voice, he lashes out at the intruder Edek, chasing him out of the house. But fate will prove Edek right, a cunning young dictator who knows how to take advantage of the situation. From a sui generis rebel, Artúr becomes a loser, a victim of his own ideas and desire for reform, unable to accept the order of this world, its debauchery, corruption, and degradation of values. Innocent, pure of heart, coming of age, he wants to restore the principles and traditional moral landmarks that have fallen into disuse, so that he has something to fall back on. Without moral landmarks, the world seems to him to be a disgusting and revolting anarchy. Artúr is a tormented idealist, of Hamletian lineage. Associations have been made in this regard, and the reference remains valid for what the Cluj show brings out of the character. Gedő Zsolt manages to convey all this turmoil through an internalized, tense performance, bordering on the unbearable.

Adrian Țion: Un dans macabru [A danse macabre], liternet.ro, June 2025

Date of the opening: May 30, 2025

Artúr, a young university student dreaming of a new world order, searches for guidance in the intellectual legacy of his parents and grandparents. But as soon as he sets out on his quest, he hits a wall, because the values he would draw on have been eroded by time: amid the accumulated reflexes of generations, tradition has become ridiculous, freedom a routine, and rebellion a fashion statement. Mrozek's Tango is not just a grotesque vision of a family drama, but also a miniature replica of a social structure, a diagnosis of the state of the world. It is a stage of civilization where there is little left behind the fantasies of salvation and the idea of freedom, where radicalism returns to the same place: power. What makes a new world order real? Can it be moral if it goes against human nature? And if all values have been exhausted, are we witnessing the birth of a new world, or are we merely replaying a bitter ritual of eternal repetition?

Réka Szabó, the play's dramaturge

Copyright has been provided on behalf of the author’s heirs by Diogenes Verlag AG (CH) and Hofra Kft.

Due to the use of powerful audio effects, the performance is not recommended for pregnant women and those who have pacemakers.