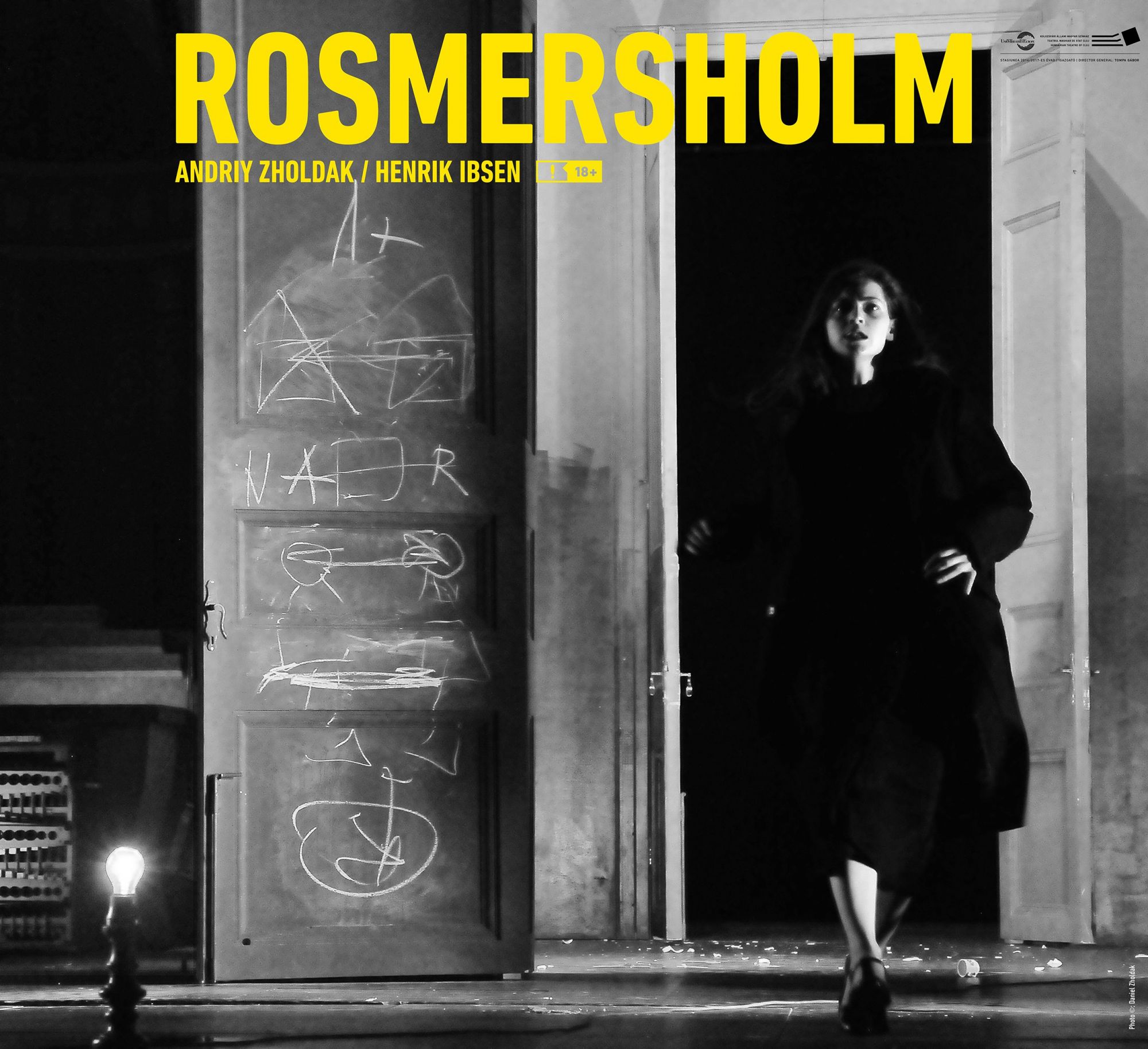

The first image (scenography by Andriy and Daniel Zholdak) invites us to discover Rosmer’s property, for in the background a hill is depicted with a few houses clinging on the hillside: an enclosed world, a citadel that holds its prisoners in extreme isolation. Pastor Rosmer (Bodolai Balázs is distinguished by a modern, fluid type of acting) and Rebekka (Éva Imre, brilliant! A true revelation!), the young girl attendant, spend their days here after the suicide of Beate, the mentally fragile wife.

(…)

Zholdak does not stage a text pragmatically and systematically, but comments it, develops its human resonance; he places it in a new dimension. Therefore, the performance often extends in duration, exceeding the standard length permitted in Eastern Europe, for the West not only accepts but also cultivates long performances, genuine invitations for the multiple hour-long explorations of certain destinies and stories. Here, Zholdak cut an important piece of the text without it losing its logic, the logic of passion that is manifested without restraint and which causes tragic situations. Thus, however, the dimension of political debates that shake up the Ibsenian text disappears completely, namely the struggle between intransigent liberal and conservative partisans. Here we only follow the wildfires of the body with everything they see as a risk in a world obsessed with sin, with guilt and, at the same time, with dissimulation.

In Zholdak’s production we find passion, visceral elements, uncontrolled and at times perverse impulses. We find the same valuation of Beate's ghost, the woman who is in the way of Rosmer and Rebecca's happiness even beyond death. The ghost-woman whose constant presence sabotages their lives. (...) However, it is not only Beata's haunting ghost that lies in the way of Rebecca and Rosmer's happiness. Their happiness appears to depend also on God’s will (many key situations are played in front of the family chapel or in the vicinity of statues evoking Biblical characters and scenes) and the pressure of the outside world. The latter is highlighted by the two people condemned a priori to a life of misery, and then to suicide.

(...)

In my opinion, a prime, substantial, and far too exacerbated deregulation of the rhythm and matrix, with a remarkably great price paid for its physiology, if not eschatology, occurs during the dinner scene. Mrs. Helseth impetuously pours the soup, Rosmer devours it like an animal. Henceforth, Zholdak's spirit has come into being. This spirit sometimes being equal to unmeasurableness. With downright going overboard. From here on, everything in the direction is different. Harsh, pathetic, Artaudian, eclectic, accentuated tones, utterance and colors. The above-mentioned eclecticism involves a bizarre mixture of things, moments, ultimately without any significance, as well as sequences marked by genius. All that is good in Andriy Zholdak's conception of the performance is undoubtedly ennobled by the excellent team of actors who make up the exceptional cast of this performance. I will repeat their names, with deep reverence, and solidarity - Balázs Bodolai, Éva Imre (a revelation!), Rita Sigmond, Gábor Viola, Gizella Kicsid.

The house is haunted by the ghost of the dead woman, and Kroll, the brother of the deceased, reveals Rebecca's incestuous relationship, pricking the heroine’s conscience and heightening the tension accumulated over time among the characters, between the walls of the house. Zholdak listens to the "voice" of this old house and builds an adequate space for these brutal confrontations. On the one hand, great salons with doors and a window of huge dimensions, on the other hand, the family chapel as a space of meditation, emptied of Christian symbols, after the priest confesses that he no longer believes in God. Undoubtedly, a spiritual void is created, one that is impossible to overcome. Huge sheet curtains cover the two spaces that appear to us alternately, betraying the oscillations of the characters themselves, who are adrift, engaged in continuous search. The window to the left of the stage, with the flowers on the windowsill placed in vases and jars, becomes a scenic metaphor of fear itself. The wind knocks over the flowers, which are at times massacred by anger, while at other times put in place to restore the order of the world. A prolonged, throbbing rumbling is heard through window space to the end, implying torture or an imminent danger, always postponed, augmented by the repetition of Rebekka's intention to commit suicide, an act encouraged by Johannes. Vladimir Klykov's music amplifies the state of violent fear woven into the shadow of past death and the possibility of a present death. Everything vibrates in this perimeter of anxieties and decisive confrontations.

(...)

The director manages to induce this state of permanent restlessness in the spectator by dislocating the real, classical plane to a highly personalized, symbolic, surreal language. I doubt not the obvious expressiveness of this jump in the realm of symbols, but that of linking the two planes. When a certain scene does not involve much dialogue, the nonverbal plane moves freely and indiscriminately into the desired semantics of gestures. When the dialogue is interrupted and there is an expansion of it in the nonverbal realm, the approach seems tautological and the return to dialogue gives the impression of being "glued back", although the language communicates as a whole, the atmosphere being maintained at turbulent heights. (...) Zholdak's vision of Ibsen’s Rosmersholm (a three-and-a-half-hour performance!) is a heavily inflated from a visual standpoint, a clear testimony of the directorial style gained and successfully promoted upon the stages where he worked thus far.

Those who did not leave, welcomed almost-midnight, which incidentally coincided with the end of the play, with standing ovations and loud cheers for the formidable Éva Imre, a Rebecca who will haunt us for a long time. Not that the Balázs Bodolai's pastor would have been inferior. That «I'm not afraid anymore!!!» in three languages, which lasted for more than a minute at the end of the first part (...), deserves a place in theatrical anthology.

The tense passivity of the original text creates the impression of a perverse, contagious discourse by which the characters contaminate each other; in Zholdak’s staging this becomes a violent energy invested in the other in the form of a form of aggression that is not contained at the simple level of discourse. Thus, mutual contamination also occurs as a permanent physical aggression, in the sense that the discourse itself becomes a corporeal fact. From this perspective, the bodies of actors are not merely simple channels of transmission for absurd or incomprehensible ideas, but become a subject whose autonomous existence in the world makes the actors' own discourse become visceral to the absurd.

Rosmersholm carefully controls the viewer – at times you understand and remain aware, while at other times you lose yourself in the performance offered. Zholdak employs to different degrees the involvement of the audience: at times he lets you consume certain moments and dissect their symbolism in your mind, while at other times he makes you abandon the rational realm by giving you emotional impulses (for when someone yells at you for several dozen minutes, you cannot not be a little bit troubled). This was the precise thing that I liked in the production: I was dizzy when I left the room at intermission and at the end of the performance when I went for a smoke. The harder he tries to push you away, the stronger he pulls you into his violent and fascinating universe.

Zholdak's production of Rosmersholm has such a powerful internal combustion that it auto combusts. Flower vases are broken, cups are destroyed, food is thrown - matter is subjected to torture, sometimes unjustifiably. Even the immaterial joins this massive pattern of destruction through the storm that begins and enters through the enormous window that looks upon the pond. To which the rain of stone is added twice as an effect. All internal fire is transmitted through a sense of distance, of “coldness”. The sense of internalisation remains to be compensated by these extreme gestures. The internal cry is actually a roar felt deep in your eardrum. According to Zholdak's vision, Rosmersholm is like a visible collapse of a house over its own masters. And as in any collapse, everything is noisy and painful.

The soundtrack of “Rosmersholm” contributes to the creation and maintenance of the horror effect: as if behind the walls of that house, which seems to be doomed, the darkness started to reign, and its servants are continually banging at its old, cracked doors. (...)

In this performance, the pivotal change of the main character is connected to the renunciation of sexuality and of the feeling of love, which are fundamental to human nature. Instead of climbing up to the top of the mountain, jus like one of the heroine’s in Wyatt's paintings, she puts one her heavy boots and gets on her bicycle to go away as far as possible from there, for good. Instead of a summer evening and the multitude of wild flowers on the window sill, suddenly a cold wind blows, and outside the immense whiteness of winter reigns.

The performance is based on precisely planned movements, as a meticulously composed complex musical piece that always sounds the same. (...) During the performance, I felt that the enormous energies that were created on stage impacted me so much so that I could not ignore even the smallest details of the events unfolding on stage, since every small nook or movement has its own significance.