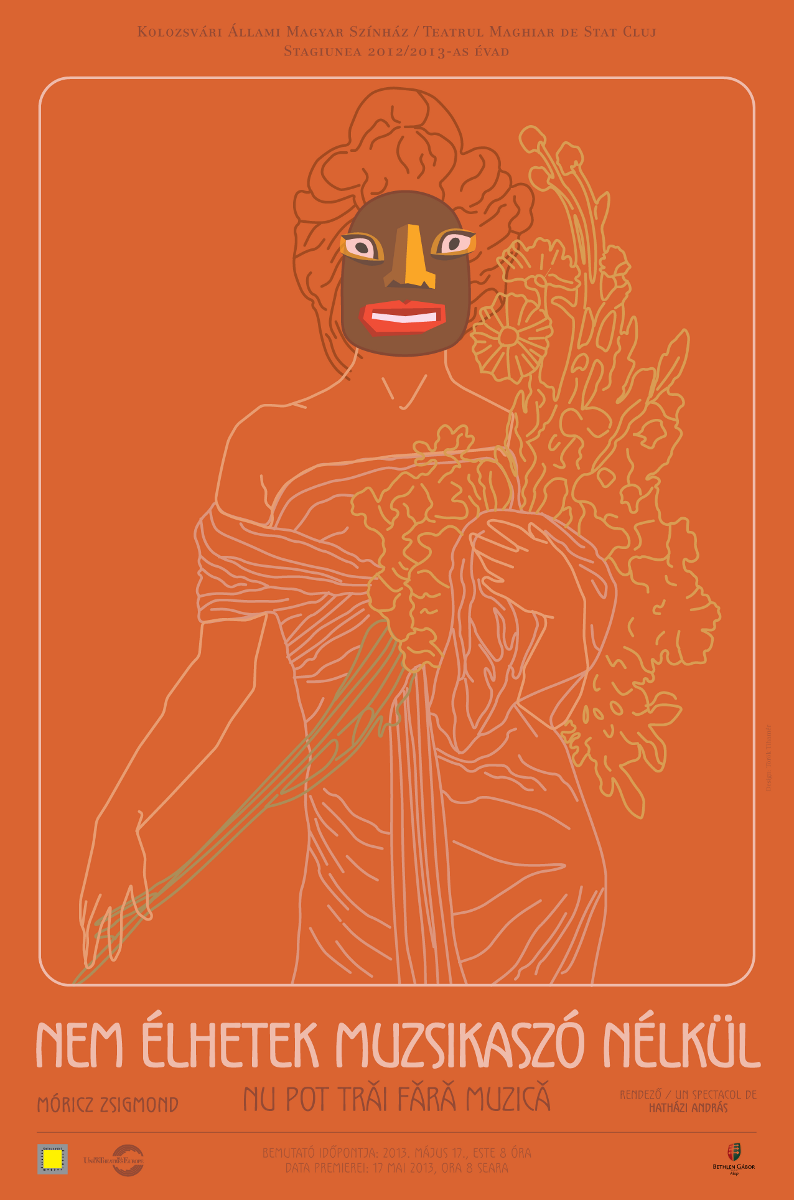

Zsigmond Móricz

I Can't Live Without Music

Main stage

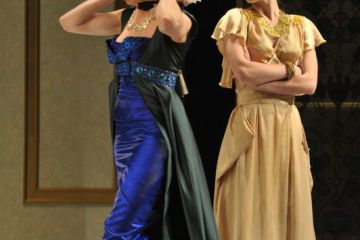

Balázs, landowner

Loránd Farkas

Pólika, his wife

Éva Imre

Auntie Zsani

Emőke Kató

Auntie Pepi

Csilla Albert

Auntie Mina

Imola Kézdi

Uncle Lajos

Ervin Szűcs

Biri

Rita Sigmond

Veronika, happy widow

Enikő Györgyjakab

Auntie Teréz, her mother

Andrea Vindis

Viktor, jurist from Budapest

Zsolt Vatány

Auntie Málcsi, her mother

Zsuzsanna Pákai

First dame

Réka Zongor

Second dame

Réka Nagy Pál

Third dame

Patrícia Puzsa

Fourth dame

Alíz Incze

First gent

András Buzási

Second gent

Csongor Köllő

Borcsa, the cooking lady

Andrea Kali / Krisztina Bíró

Zsuzsi, maid

Júlia Bíró

Gergő, old coachman

Ferenc Sinkó

Peták, do-all

Levente Molnár

Kati, maid

Enikő Molnár

Mircse, gipsy musician

Attila Pál

Mrs Kisvicák

Csilla Varga

Pista, stripling

Csaba Marosán

Auntie Mariska

Brigitta Nánási

Gazsi, clarinettist

Péter Árus

Lali, bassist

Szabolcs Balla

directed by

András Hatházi set design

Carmencita Brojboiu costume design

Eszter György dramaturg

Eszter György stage manager

Imola Kerezsy

Loránd Farkas

Éva Imre

Emőke Kató

Csilla Albert

Imola Kézdi

Ervin Szűcs

Rita Sigmond

Enikő Györgyjakab

Andrea Vindis

Zsolt Vatány

Zsuzsanna Pákai

Réka Zongor

Réka Nagy Pál

Patrícia Puzsa

Alíz Incze

András Buzási

Csongor Köllő

Andrea Kali / Krisztina Bíró

Júlia Bíró

Ferenc Sinkó

Levente Molnár

Enikő Molnár

Attila Pál

Csilla Varga

Csaba Marosán

Brigitta Nánási

Péter Árus

Szabolcs Balla

directed by

András Hatházi

Carmencita Brojboiu

Eszter György

Eszter György

Imola Kerezsy

Date of the opening: May 17, 2013

Date of creation: 17 May 2013Duration: 3 hours with one intermission

It’s not certain that what we say, is what there is.

It’s not certain that it’s good to know something beforehand.

Everything changes, but especially us.

The personality, or at least how we think of it, is not a homogeneous, unchangeable entity, but merely a dynamic, situation-dependent, ever changing guard-rail that we create in self-defense against the world outside us. (And there is a special luck and virtue in our creating it. We could have a chance to participate in the future discovery and development of our essence! I tend to think that we learn forms of conduct by close observation; we refine the patterns of others, shaping them, tailoring them for ourselves.) Consequently, there’s no single I, and we can never say that we are whom we think we are. It’s true that we react in a unique way to never-changing human situations, but eventually we come to do so mechanically. But, whenever we lose our balance a little bit, we instantly panic and consider our situation to be extreme. We “lose” our “personality”, we “turn inside out” and, dragging our whole existence into danger, we desperately try to fill the gap through which the outside world may find a way toward us. Anything can threaten us – a sudden fatal event, or falling in love – but regardless of how we live the moment, positively or negatively, we’ll suddenly have the option to react differently. Suddenly we experience freedom.

In my interpretation, this is what theatre events are about. About people who suddenly find themselves in situations where their automatic behavior loses its meaning and they are forced to act in an unusual way by things going on around them and affecting them immediately. At such times categories do not exist a priori, but a posteriori. The situation can be evaluated only at a later point and participants in the event can be characterized as being this and that only after getting through it. But this belongs to the past, and theatre’s time is exclusively the now, the unpossessable – in the full sense of the word – present.

So then, how could this still be possible?

I don’t know.

In any case, this is not what I expected regarding Muzsikaszó...

András Hatházi