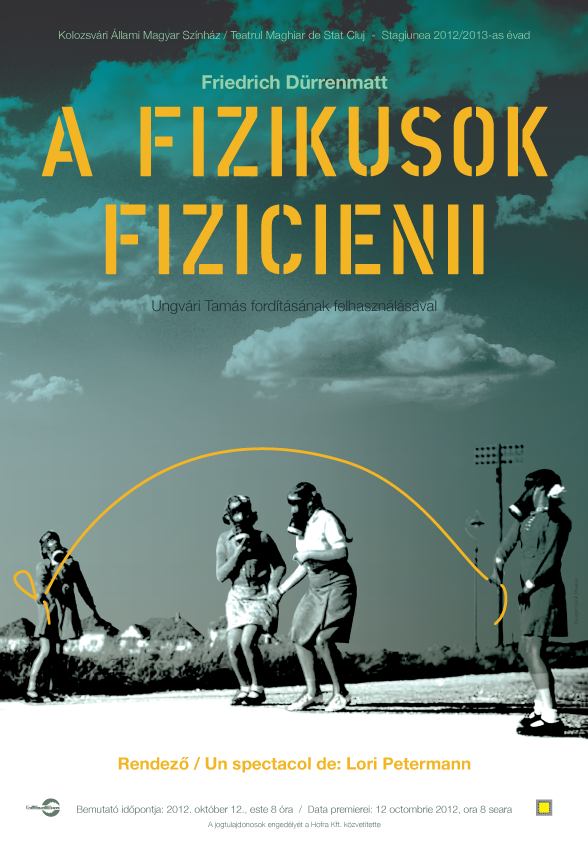

Friedrich Dürrenmatt

The Physicists

Main stage

Mathilde von Zahnd

Emőke Kató

Herbert Georg Beutler, or Newton

Lóránd Váta

Ernst Heinrich Ernesti, or Einstein

Levente Molnár

Johann-Wilhelm Möbius

Áron Dimény

Martha Boll

Tünde Skovrán

Oscar Ruse, Uwe Sievers, head nurse

Sándor Keresztes

Supervisor Richard Voss

Ervin Szűcs

Nurse Monika Stettler

Anikó Pethő

Lina Rose, nurse

Csilla Varga

Irene Staub, young Rose

Andrea Vindis

Nurse, Dorothea Moser, Jörg-Lukas

Melinda Kántor

Adolphe Friedrich, policeman, nurse

Loránd Farkas

Guhl, Wilfred-Kaspar, nurse

Balázs Bodolai

Blocher, young Rose, nurse

Csongor Köllő

Murillo, young Rose, policeman

András Buzási

McArthur, young Rose, policeman

Szabolcs Balla

Young Rose, nurse, policeman

Alpár Fogarasi

directed by

Lori Petermann set design

Steven C. Kemp costume design

Emily DeAngelis dramaturg

Emily Deangelis stage manager

Györffy Zsolt

Emőke Kató

Lóránd Váta

Levente Molnár

Áron Dimény

Tünde Skovrán

Sándor Keresztes

Ervin Szűcs

Anikó Pethő

Csilla Varga

Andrea Vindis

Melinda Kántor

Loránd Farkas

Balázs Bodolai

Csongor Köllő

András Buzási

Szabolcs Balla

Alpár Fogarasi

directed by

Lori Petermann

Steven C. Kemp

Emily DeAngelis

Emily Deangelis

Györffy Zsolt

Date of the opening: October 12, 2012

Date of opening: 12 October 2012 Duration: 2 hours 40 minutes with one intermission

Interview with director Lori Petermann

License mediated by Hofra Kft.

“I can picture in my mind a world without war, a world without hate. And I can picture us attacking that world, because they would never expect it.”

- Jack Handey (Deep Thoughts)

The Physicists is a provocative and darkly comic satire reflecting the conflicts and fears that arise when countries are all competing for the latest and most advanced technologies for warfare.

The world’s greatest physicist Johann Wilhelm Möbius is committed to an isolated asylum and proclaims to be haunted by recurring visions of King Solomon. His company in the asylum is two other equally deluded physicists: one who thinks he is Albert Einstein, another who believes he is Sir Isaac Newton. However, it soon becomes evident that these three are not the harmless lunatics they appear to be. Added to this treacherous combination is the world-renowned psychiatrist in charge, the hunchbacked Dr. Mathilde Von Zahnd, who has some diabolical plans of her own.

Dürrenmatt and I, although we have lived in different eras, share a common understanding and fear. In reflecting on the state of the world we have both found ourselves in a state horror. As a young adult in

Since Dürrenmatt lived before my time, I am jolted by the trepidation that the situation has not improved but has instead has gotten worse. As countries continue to compete for the latest and most advanced technologies for warfare, it seems to me that the faces have changed, but the circumstances have only grown more severe. The very present threats of terrorists and biological warfare are something that I have experienced first hand living in the present day. The vivid anxiety of living in

Amongst this darkness, there is another commonality that I share with Durrenmatt, which is that, “what concerns everyone can only be resolved by everyone.” – as he proclaims in his 21 Points to The Physicists. This for me is where the theater becomes an essential tool. The theater becomes a forum to express these fears and expose the conflicts of the current cultural climate. It is not an attempt to preach or to force a resolve, but to create an outlet, to share with a microcosm of the “everyone” - in hopes that the major goal of broadening a universal perspective will in itself generate progress. In my eyes, no better place than a sanatorium to truly see the world in reflection. Equally, to venture boldly into the darkness, there is no better invitation than humor. Durrenmatt states, “to present the pure tragic is impossible in the grotesque time, unless we achieve the tragic out of comedy.” Although this may seem paradoxical, it is honest and humane to those whom which it is essential that we reach. And truly begs the question, who is truly insane? Is it the scientific “madmen” who bear the guilt and moral burden of their discoveries or the political figures that run our countries and exploit such discoveries?

Lori Petermann