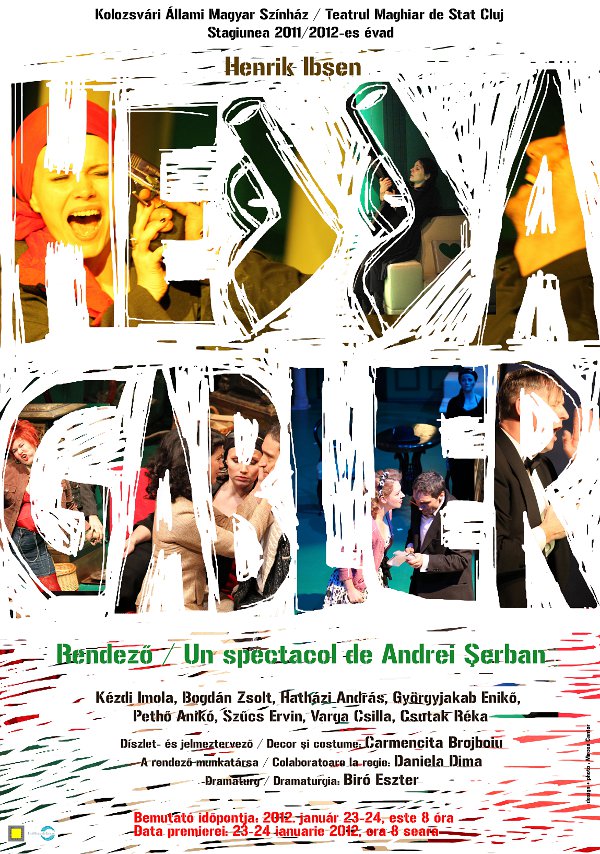

Throw every review to the fjord, to the Olt, to the Someş: no analysis can be compared to a single movement of Hedda Gabler’s (Imola Kézdi) eyebrow. Still, one has to talk it out, understand, and the need for talking it out and understanding also needs to be talked about and be understood. And one has to laugh, to defeat or at least domesticate our biggest fear: we are all frustrated, depressed, messed up, scheming, evil and two faced, just like Hedda Gabler.

Hedda’s biggest problem can be called banal: she finds no one who understands her. But it is her superiority complex that makes her incapable of ever letting anyone close to her. Her tragedy: she has no one, neither in her life, nor in her death, only her pistols and her pride.

From a spoiled aryan little girl, she has grown into an eccentric, cruel woman. Her only idol is her dead father. She would have liked a companion, but couldn’t find a worthy partner. Her marriage is a financial disaster, her husband (Zsolt Bogdán), a childish no one. She traps, seduces and pushes away Lövborg (Ervin Szűcs) after he fails. What she really needs is a new idol in the pantheon next to the general, a heroic lover with vine leaves on his forehead, and the alcoholic Lövborg would only fit this role if he were dead. Maybe not even then.

Hedda could have been an Amazon, a Spartan warrior or a Kill Bill-bride but she was thrown into the wrong time, the wrong era, surrounded by the wrong people, where she has no chance of fulfilling herself, of living up to her energy and her talent. People are terrified by her fearlessness, they are offended by her being distant, they assault her refined taste with kitsch and her sophistication with harshness. In the luxurious apartment that has been arranged for her she lives like a beautiful big cat in a cage. First people are afraid of her, they respect her, they tiptoe around her and try to fulfill all her eccentric wishes, and then – just as she gets bored with her life that lacks challenges, and triggers the action that eventually leads to her destiny – they become bored with her. She moults her shiny heroism in clumps as she experiences humiliation. There is only one way to restore her integrity: she shoots herself in the temple, beautifully, as it is supposed to be done, wearing a general’s uniform. The others celebrate, are happy, and laugh when she steps out from among then: order is restored, as she was never one of them anyway.

Throughout the whole play there is a conflict of values between Hedda and the other characters. And the viewer wavers in this force field. Now we feel compassion for Hedda, then we feel sorry for the professor, Thea or Lövborg. The person for whom we feel compassion changes so subtly, with our laughter, that we might not even realize, how confused we are. Mediocrity wins, the tragic hero fails, the riffraff screams with laughter. But it is all right like this, Hedda doesn’t need our compassion, her smile is bloody, shiny and glorious. Even if she could not understand herself, she manages to defeat herself, only worthy enemy.

So, who is Hedda Gabler, and why is she like this? No matter how hard I would try, I would not be able to give definite answers. What I am sure of is that Imola Kézdi, with her understanding of her role, with her minutely elaborated interpretation, is able to raise these issues among the audience. Consequently, we witness a very complex, well-considered, outstanding performance.

She has splendid partners in accomplishing this. Let’s start, first of all, with her husband Jörgen Tesman, played by Zsolt Bogdán. It’s true that, for the extent of a parenthesis, I will contradict myself, because I must mention the fear that took hold of me for a while: namely, that this wonderful actor seemed to get stuck in self-repetition, since in the first ten to fifteen minutes I saw the same tried and tested gestures that I had seen in some previous performances (for example Yakobi and Leidental or the recently presented King Ubu). As the production progressed, however, his play became more and more interesting, colourful and very entertaining. Zsolt Bogdán could change almost instantly, showing Jörgen Tesman’s helplessness, his stumbling powerlessness, laying emphasis on the character as a petty “eternal child” raised by his aunts, incapable of growing up and, at the same time, a mediocre scientist. Pampered and spoiled by his aunts, Tesman becomes unspeakably upset if people don’t treat him as he expects them to. His reaction to one of Hedda’s remarks is like the “feigned hysteria of a woman”. Then, in a split second, he calms down, as if he were using some kind of treatment suggested by a psychologist upon himself. He immediately adapts to Hedda’s change of disposition, but he is able to replace her in an equally rapid way. Hedda’s death means no loss for him, since the self-sacrificing Mrs. Elvsted has already taken her place.

Judge Brack (András Hatházi) is also a central figure in the play. He tries to find favour with the newlyweds by doing things that are useful since, according to his values, a smoothly functioning triangle is worth gold. It seems this would satisfy Tesman, also. Only Hedda has to be convinced and success would be complete. Brack does not shrink from any means. First, he tries subtly to induce Hedda to accept this game. Then, he blackmails her, bribes and finally, gently threatens her. He presents his judicial shrewdness in such a way that it takes some time for us to realize his wiles. András Hatházi is an excellent Brack. He constructs the role very well and is very careful to not let us feel an aversion to him for too long.

We have two Mrs. Elvsteds in the cast, Enikő Györgyjakab and Anikó Pethő. In their interpretations we meet a character who, no matter how dull she appears next to Hedda, is “a task to be solved” by her. Hedda employs all kinds of means in combat with her, in order to overcome her. The self-sacrificing Mrs. Elvsted does not seem to be aware of this. She is afraid of Hedda and, being a little stupid, she becomes an excellent ground for Hedda; the dark side of her character becomes more evident in the scenes involving both of them. Both actresses build up the role nicely although using different means, a job well done.

Ervin Szűcs in the role of Eljert Lövborg is convincing, although he gets off to a slow start. It might be due to the reserved nature of the character he has to play, since Lövborg knows very well that meeting Hedda again is a dangerous game. In the second half of the performance, however, Ervin Szűcs is relieved of all inhibitions and presents us with an excellent Lövborg.

I would also mention Csilla Varga, who plays the role of the aunt, Juliane Tesman (also the role of Mademoiselle Diana for a short time), and Réka Csutak who plays Berte. Both of them integrate well into this performance, displaying excellent theatrical work.

Katalin Köllő: Ki is ez a Hedda Gabler? [Who, in fact, is Hedda Gabler?], Szabadság, February 4, 2012

The director of the play cut out the intermissions. While the length of the drama offers this possibility, his decision makes the story more concentrated and the audience much more involved. Jörgen Tesman’s (Zsolt Bogdán) antics and sang-froid make the play compelling. This intellectual young man with scientific aspirations, while not necessarily a genius, becomes a sort of buffoon in Andrei Şerban’s production. His gestures often trigger laughter. He embodies the awkwardness of the character that he plays, whom Hedda can relate to only as a partner but not as wife.

Hedda’s inner world remains foreign to Tesman. Ibsen, incidentally, mentions somewhere that in using Hedda’s maiden name as the title of the play, he wanted to indicate that Hedda has an independent personality. She is more “her father’s daughter” than she is Tesman’s wife. The influence of Hedda’s father on his daughter is emphasized by introducing the voice of General Gabler (recorded by József Biró) in the play. Andrei Şerban explained that similar to Chekov’s “three sisters”, Hedda also is suffering from “the soldierly prejudices of an authority represented exclusively by men”, from the sickening effect of “rigid and sultry conformity”.

Northern frigidity is Americanized by Andrei Şerban through the style of films and advertisements of 1950's American middle-class life. But somehow the Russian world, the world of Chekhov, also marks the production, the victory of melancholy and the tragic grotesque of Andrei Şerban's staging.

As the director puts it, it’s impossible to present the play as it was in 1891, at the time of the German opening performance, at the time of the fin de siècle which was heavily shaken by cynicism, middle-class boredom and decadence. Of course, even a century later many things remain the same, but they don’t vibrate in the same tessitura. We can no longer tolerate the theatrical floor boards, the box seats, the monocle and the frock-coat. Present-day theatre has to be among us in the studio performances of Andrei Şerban, where actors turn into savages one meter away from us, where they touch us lightly with their overcoats as they turn around, and where we take fright at their swords (even if all this is replaced mostly with modern costumes and guns borrowed from action films).

The director presents an unusual interpretation. Instead of staging the play in a dramatic way as it has been done before, he places it in the space of tragi-comedy or, to put it better, in the space between tragedy and comedy. Why this clear line of separation? Andrei Șerban builds the personality of the characters upon the psychotic conflict within themselves, from Hedda (Imola Kézdi plays her role in a captivating way) to Tesman (Zsolt Bogdán) and Løvborg (Ervin Szűcs, a new member of the Hungarian theatre’s company who was absent from the previous [Șerban] productions); from Thea Elvsted (I saw the play with Enikő Györgyjakab; the other actress, in this double cast, is Anikó Pethő) to Judge Brack (András Hatházi). He constructs the play upon tragic moments that follow the pure comedy aggressively with a sudden change of behaviour – every trait jumps out of the store and shows itself cyclically, with a geometrical exactitude. The characters are fragmentary, their features are preposterously enlarged – notice the distorting mirror at the back of the set that is the visual representation of the actors’ performance, Tesman’s childish behavior in the first half, or Brack’s hyena-like attitude at the end when he finally discovers how he can get closer to Hedda, even if it is by blackmailing her. The comic element created by the use of American music from the 1950’s and the 1960’s (Guy Mitchell, Nat 'King' Cole, Danny and the Juniors, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Marilyn Monroe and, in the last scene, Frank Sinatra), the background music that is managed by the actors using a record player in one of the corners of the stage, falls constantly apart. It becomes fragmentary in the recurring tragedy of the scenes that gravitate towards Hedda. In the second half of the play, this music is completed by Hedda’s own, grave musical motif.

Paul Boca: Andrei Şerban la Teatrul Maghiar: o continuare în verde – Hedda Gabler [Andrei Şerban at the Hungarian Theatre: Continuation in green], ArtAct Magazine, January 25, 2012

The charm of the scenes lies in their parts, in the gestures, play and mimicry of the actors. In one of the episodes where Brack steals into Hedda’s life, the actors switch the wall lamp in the room on and off. As if the neurons in Hedda’s complicated mind become excited and then slacken as a result of those stimuli – money, honesty, beauty – that rule her nature.

Bianca Felseghi: Hedda Gabler, la Teatrul Maghiar: povestea onoarei sufocate de mediocritate şi de jumătăţile de adevăr [Hedda Gabler at the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj: a story of honour suffocated by mediocrity and half-truths], Ora de Ştiri, January 20, 2012

Imola Kézdi’s Hedda Gabler [appearing] in the Cluj studio is a charming monster. She is capable of doing anything out of whimsy. Her ideas, which come from boredom and aimlessness, shake her whole environment. She alone is unmoved by them. Nothing and no one can make her happy, and this unhappiness torments everyone whom she touches. The excellent performance is an unfolding analysis of this unhappiness, an extensive study of its comedy and the telling of its tragedy. What at first seems to be simply a bad mood and irritation fulfills itself as character and destiny in the tragic game in which she is destroying herself. Hedda longs for an incomprehensible, indefinable action, gesture, value, just as Camus’ Caligula longs for the moon. Imola Kézdi’s every small movement sensitively follows a path that is lined by ridiculous characters and that takes us through many funny scenes.

In Andrei Şerban’s mise en scene, it is not only the pistols inherited from her father that play a symbolic role, but also the vine leaves which Hedda imagines on the hair of the scholar – sometimes he's a genius, sometimes he descends into alcoholism, her former lover and her husband’s rival – as he fulfills his beautiful, clean self-destructive act. As we enter the space we trample on yellow vine leaves that lie on the ground like the leaves of autumn, and these leaves keep encroaching into the story. People who enter keep kicking them up and Hedda’s childishly accurate husband startledly sweeps them out.

This time the director doesn’t imagine a new world to replace the original story, the Norwegian bourgeois world of the 20th century. But he doesn’t stick to it either. Carmencita Brojboiu’s scenery and costumes evoke that age in the details, but also create a distance from it. The clothes serve primarily not the age, but the characters. Music plays a great part. Sometimes it is heard live from the piano and sometimes from recordings, as Hedda turns on the record player, adjusting the atmosphere to her own intentions behind the words.

When you say Andrei Şerban, you unconsciously become curious about the directorial process through which he succeeds in renewing plays that have no appeal left for the public, due to the wicked present. (...) The performance not only renounces the heavy and realistic tone set by the dramaturg, but understands the contemporary lightness and appetite for playing, without losing its value. When I say playing, I mean the humour which Andrei Şerban constructs with great carefulness in every scene. Of course, we are not simply speaking about humour! And that is precisely because of the Ibsenian meaning that Andrei Şerban preserves even within the humorous structure of the performance Hedda Gabler.

At the Hungarian Theatre, Andrei Şerban and Carmencita Brojboiu bring flores para los muertos in spotted bouquets, violent in colour, covering discordant pieces of furniture, some of them adapted to Ibsen’s era, some of them intentionally incongruous in time. Unveiled of the bloody linen [draping them] – a simulation of passion, in fact a place of blood, as it was in Cries and Whispers – they prove to be the mass-produced furniture of our day, and the mirror reflects the viewer of the 21st century. All are set in a uniform background of cold green, conjuring the plain velvet of the Ibsenian middle class, its restlessness expressed by a constant dance of the furniture, which is moved in every scene to a different corner of the drawing room.

The performance received three UNITER (Romanian Theatre Union) awards in 2012: Best actress of the year (Imola Kézdi), Best actress of the year in a supporting role (Enikő Györgyjakab) and Best actor of the year in a supporting role (András Hatházi).