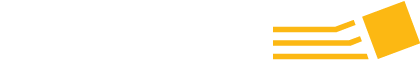

The encounter between Kinga Mezei (the director) and Angi Máté (the author of the novel Mamó) marks a special type of communication from the standpoint of mutual sensibilities and spiritual appeal, possibly related also to a common cultural background, which includes, among other ingredients, being a member of a traditional minority. Kinga Mezei comes from Serbia (she studied at Novi Sad), while Angi Máté was born in Hunedoara, Transilvania. The “Lace” crocheted by these two young women in the form of memory sequences highlight a world left behind in the past, nestled in the magic of childhood. These scenes that have been pulled from the novel are stitched in the mind of an orphan child, who was raised by her grandmother and rendered on stage as subunits of a mysterious mechanism, full of life. The poetry of the writing transpires only vaguely through the performance due to the emphasis places on the comical, still, it is partially recovered by the music score, adequate from the standpoint of the melodic line, but not illustrative, used also as a link between the character Angi and her recollections. Lace is a confession in the form of a performance, which has a certain compositional lightness and emotional finesse, built around the monologue of the little orphan girl, wonderfully portrayed by Enikő Györgyjakab.

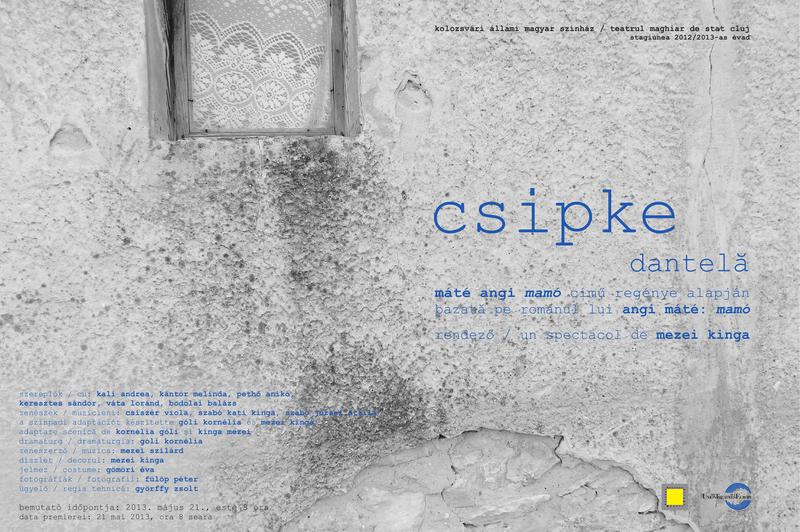

We are dealing with a well-elaborated theatrical production, with carefully composed details, which nonetheless do not hinder the ease of the performance, one which lingers above the earth, and convinces us of the following: there is no need for bright lights to be shone in the eyes of the audience, nor there is need for vulgar expression in order to bring a (pleasantly) surprising, new play to the stage. (...) It portrays an enclosed, heavy, still lightly levitating world, which is pervaded by the specific, open worldview of a child. We are amazed to realize that such a world also exists, while we, the audience, also take over the sincerity of a child’s openness, as we start floating, letting the performance leave countless, scintillating marks in us, for as we suspected at the beginning: the marks left behind by this performance will stay with the audience long after its end. (...) The waving and levitation constructed by the procession of images define the entirety of the performance, as well as the actor’s portrayals, and are also well suited to the elements meant for spatial delineation, such as the white curtains, the canvases, the images projected on these canvases, or the shadows that appear behind them. During the entire duration of the play one treads on the boundary between remembrances, reality and dreams.

Zsolt Karácsonyi: A ritmussá lett láthatatlan [The Invisible Transposed into Rhythm], Helikon, 25 July 2013

Lace does not slip into sentimentality, it accentuates the humor and playfulness present also within the book, and does not neglect the lyrical aspect of the story and of its language even for a moment. (...) Every single scene of the play contours a powerful image that works marvelously both on an individual level, but also as part of a whole. At one point we can almost sense the smell of vanilla powder and we would like to slip an orange from the Christmas pageant into our pockets.

Zsuzsa Gergely: Csipke – Máté Angi Mamója színpadon/Angi Máté’s Mamó on Stage(Donát 160), Kolozsvári Rádió

The mental world of a young girl who was forced to live an isolated life appears in front of us on stage, through images, moods and gazes: mischief and tantrums, curiosity and a hunger for love take shape in front of us. The peculiarly magical language of Andi Máté and the personality of a fragile little girl who wants to discover the world take shape within the performance just like the rhythmic gestures of the grandmother as she knits this delicate lace.

The Lace of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj (...) is completely different, from the standpoint of poetic language, speaking of the quality of being lovable beyond the world’s cruelty, whereas Angi Máté’s novel Mamó, which represents the basis for the staging of this play by director Kinga Mezei, is far from being about a happy childhood. Or rather it is: the orphan little girl protagonist (in Enikő Györgyjakab’s sensitive portrayal) colors life’s darkest moments in the humorous colors of the rainbow in her imagination, despite all the terrible things that have happened to her. We see a reality-fairytale on director Mezei’s stage, and the fairytale (together with its narrations and evocations) becomes a method of processing and understanding not only death, but also one’s life story, by way of the magical elements of language, which wrap around the pain: Angi Máté’s linguistic creations speak the truth in an almost healing, still, not a fatally sharp way.

The characters and individual stories are interwoven as a lace, Angi’s narration slowly unfolds them. For Angi finds patterns everywhere: forms of human and societal behaviors. She lives with them, they define her everyday life. The reasons and underlying causes of these patterns are formulated in her own pure way. She knows that one should wear a nice dress to church, or to a visit, and she also knows that one goes to the cemetery for others to take pity on them.

And she also knows that it is a good feeling to observe something moving.

During the performance of Lace something was moving.

And not merely on stage.

Janka Szabó: Egy frenet(n)ikus fesztiválkezdés [A Frantic Festival Beginning], színpad.ro, 2014

Kinga Mezei’s direction opens up a new type of dimension of solitude: what does an orphaned little girl do in a rustic environment, having a strict but caring grandmother by her side? This is a poetic story of becoming an adult and of self-awareness, told from a distinctly feminine perspective. The latter trait of the performance is perhaps the greatest merit of the production: during the almost 2 hours of the play, we realize the sad fact that, as viewers, without even realizing it, we have gotten used to the macho nature of female representation, that is, we have gotten used to the forceful male reading of female characters, which rarely have a place for the rather deep - but also empathic - representation we encounter within Lace.