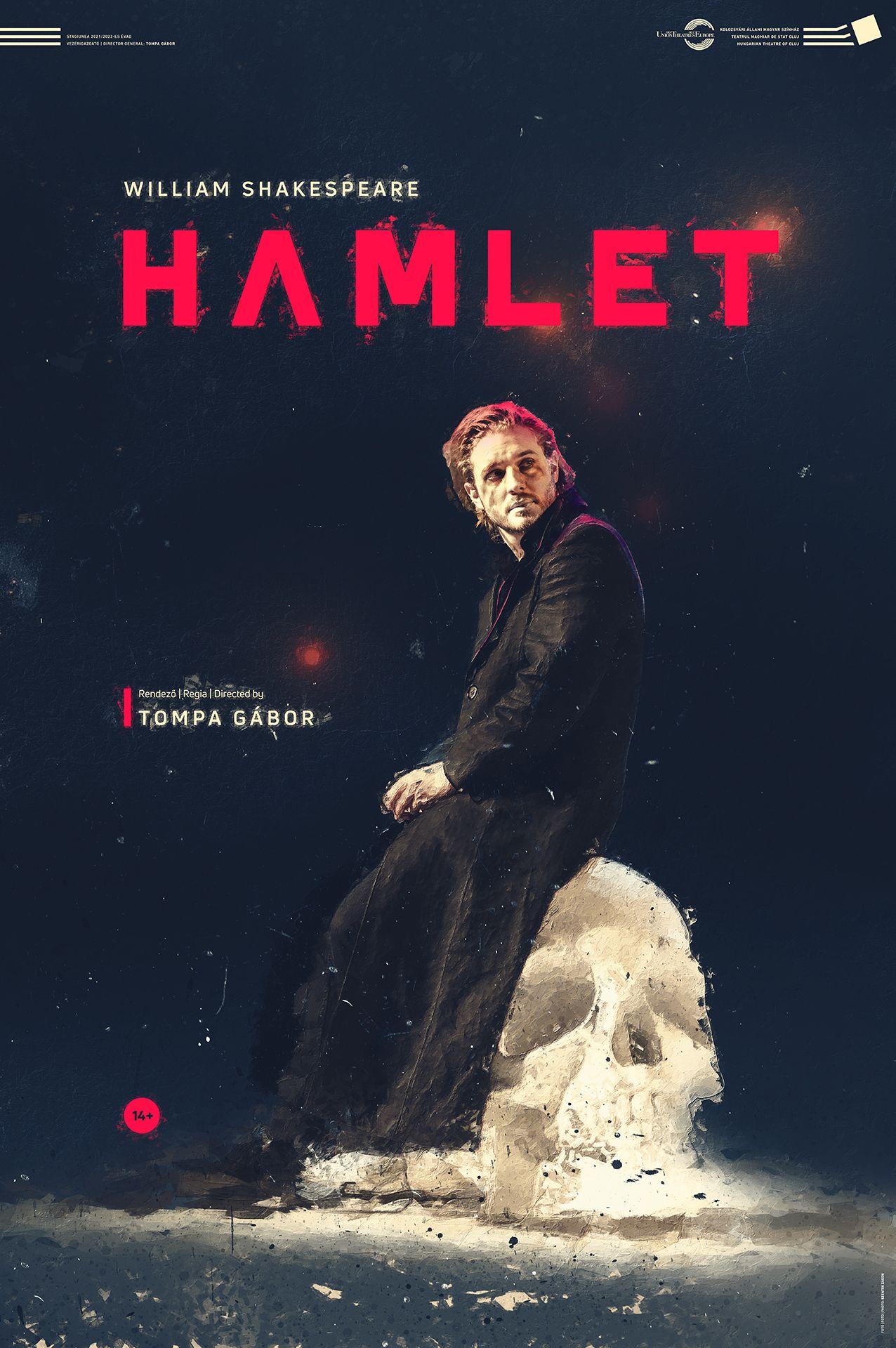

Even with their simple black costumes, Miklós Vecsei H. Vecsei's Hamlet and his Wittemberg friends are already in stark contrast with the rest of the Danish royal court, who chase their pleasures in shiny clothes and furs. In Tompa's vision, Hamlet's childhood friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are strongly sexualized women, rejected by the Danish prince, but one can suspect that they were also previously objects of his pleasure. Hamlet makes the court see him as being insane by rejecting all formality and fads, by saying what he thinks or by making inappropriate statements to highlight the absurd values his environment represents.

Erika Zsizsmann: Hamlet leszáll a futószalagról – bemutatóval indult a kolozsvári színház miniévada [Hamlet gets off the converyor-belt - the showcase of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj began with a premiere], maszol.ro, December 4, 2021.

Tompa's new Hamlet is about to lose itself in the world of the new, in the world of Claudius. Barely carried by the shoulders of his friends in Wittenberg's Bande à part and the arms of Ophelia, Hamlet gains the power to unmask the cartoon world we have come to live in. But animated by cartoons and nothing else/noBody else, the world is doomed to start all over again in the following second. It takes newer and newer Hamlets. It takes us. What about us?

Mihai Brezeanu: O lume ded agenţi zero-zero [A world of doulbe O agents] - Hamlet, liternet.ro, December 2021

Gábor Tompa's Hamlet is spectacular primarily because of the spectacular quality of his directorial solutions. One feels behind what one sees the joy of creation, the endless playfulness to which an ever-young, available and surprising creator indulges. A play that opens up, not infrequently, into serious discourse... The direction is everywhere in this show, sometimes, yes, in excess, but how adorable this excess is!

Călin Ciobotari: Din nou despre Hamlet. Versiunea Tompa Gábor… [Again about Hamlet. Tompa Gábor's version...], 7iasi.ro, December 5, 2021

In Hamlet, Gábor Tompa, in his usual way, holds up a mirror to the intricacies and erosive depths of our contemporary world. One of these directorial ideas is the treadmill on the left side of the stage, on which the queen and Hamlet "move in one place" with monotonous movements. The idea of the treadmill might suggest that we all run around like this in a mechanical, hurried world where our actions and events are often controlled and dumbed down by the need for constant repetition. Our world is fragmenting, our values, marked by books, knowledge, the desire for truth, are doomed to fall and to be destroyed - this could be symbolized by Hamlet's scattering and throwing away of the books on the shelves. And although the world is changing in many ways, human weakness, evil and thirst for power are still reappearing, controlling, destroying and abolishing, just as they did centuries ago. While the justice seeker must set out today on the same journey, fraught with doubts and pitfalls, often on a treadmill, until he reaches the final boxing match in the ultimate ring.

Judit Kiss: Világunk széttöredezik, akár a Hamleté – A fiatalokat is színházba „csalogathatja” az örök érvényű Shakespeare-dráma [Our world is fragmenting, like Hamlet's - The eternal Shakespearean drama can "lure" young people to the theatre], Krónika, December 5, 2021.

HAMLET directed by Gábor Tompa, with Miklós Vecsei H. as a guest artist in the title role, was a striking, salutary and, dare I say - as a philosophy graduate, thus inevitably part of the Wittenberg gang - ecstatic experience. Hamlet has his mother play her own role, that of the newly widowed widow turned wife of the regicide brother-in-law, and his uncle the role of the murdered father. As for Hamlet, he sees fit to play the murderer.

Hamlet commits a programmatic act, showing us theatre as maieutics and as the practice of truth. Telling the truth is the supreme temerity, for which you must give your life. Hamlet can neither run on the broken conveyor-belt of the present like his mother, fleeing from the infamous near past, throwing himself into the arms of debauchery, nor dance gently to the music of tender hopes like Ophelia.

Ana Ionesei: Hamlet, Teatrul, praxisul Adevărului [Hamlet, Theatre, the Praxis of Truth], Bookhub.ro, December 6, 2021

In his fourth staging of Shakespeare's play, Tompa did not have to confirm his talent or success, but to respond to another challenge: how to make the (Romanian) spectator forget about Adrian Pintea’s portrayal of the role? Because, let's face it, for the Romanian audience, the performance of the Craiova theatre with Pintea as Hamlet is unforgettable! Fortunately, Gábor Tompa is not one of the directors who self-plagiarize, so the four productions are as different as they are topical. One can talk a lot (and well) about the Hamlet of 2021 without exhausting the subject, and that's also a director's challenge to reviewers and other analysts.

Nona Rapotan: Hamlet – între a fi și a nu fi e loc pentru spectacolul lumii [Hamlet - between to be and not to be is also room for the spectacle of the world], Bookhub.ro, December 8, 2021

You can't help but love Hamlet, as Miklós Vecsei H. brings him to the stage. He juggles emotions and moods as fast as moves, with breathtaking speed. In a few steps he is crossing the stage, getting from one corner to the other, now weaving plots, the next moment meditating, etc. A very, very special actor with a unique ability to use emotion and intelligence in equal measure. Despite his obvious youth, he manages to take on a certain amount of maturity on the fly, which helps him to win over the Queen and lose Ophelia. At least two moments remain remarkable, one of them being his direction of the court performance, moments when he becomes the conductor of the lives of others, the master of their lives.

Nona Rapotan: Cercurile puterii sau mobilul adevăratului conflict [Circles of power or the motive of true conflict], Bookhub.ro, December 9, 2021

There will always be something artistically unexplored in Shakespeare's Hamlet. Let's go on stage, to the premiere of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj (3 December 2021, directed by Tompa Gábor (he has also staged Hamlet in Craiova and Cluj). Expectations are high, knowing the value and rigor of the director. Premiere atmosphere. Minimalist set, anguished music, accompanied by the ephemerality of waves. On the left, a treadmill, on which, from time to time, certain characters will linger, in a vain, aimless walk. A slow pace, right? When "there's something rotten" progress stagnates, behind a dictatorship, the System hides the truth, but Hamlet and his circle of friends can cause the smokescreen to collapse. Tompa does not shy away from modernizing, accentuating the violence of recession and the emptiness of a "hideous" world, which is why we witness a wicked, rhythmic dance, as a definition of the system's slippage.

Alexandru Jurcan: Hamlet pe ecran și pe scenă [Hamlet on screen and on stage], Tribuna no. 463, December, 16-31, 2021

The visual realm, András Both's trademark, creates an intense and suffocating sense of enclosure, with the box-cell serving as both a space for meditation and decisive action. It is the place where Hamlet understands the painful truth that there is no more time to get lost in thoughts and philosophies, and that the only solution destiny offers him is action; it is also the space where a whole universe dies, with its misery, its pains, its unfulfilled dreams.

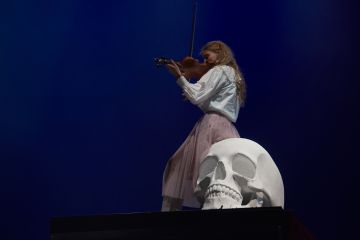

The deeply flawed world in which Ophelia's death is discussed in a podcast by her executioners themselves, a world that Hamlet is tasked with rebalancing, must be utterly demolished, for evil has insinuated itself too deeply into its every layer. There is no longer even a Horatio to carry the story forward. The duel between Laertes (Tamás Kiss) and Hamlet, fought as a boxing match in his former cell, ends in total annihilation. A carnage in which skulls remain, and above them all, an oversized skull on which an Ophelia-child (Sára Viola) plays the violin.

Silvia Dumitrache: Întîlnire 2.0 cu Shakespeare, Orwell, Ionesco și Cehov [Encounter 2.0 with Shakespeare, Orwell, Ionesco and Chekhov], observatorcultural.ro, December 16, 2021

At the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj, a pretty violin-playing girl, little Ophelia, appears, and a tiny boy, now a Danish prince, runs up to her with a bouquet of flowers. Spun on the temporal axis of memory, we see that while little Hamlet was presenting a bouquet of flowers to the slightly older Ophelia for her excellent violin playing, the fallen girl with the rounded belly was saying goodbye to her earthly life, and distributing a bouquet of human skeleton bones, one bone at a time, to the members of the Danish court. Who is it? A spellbinding being - the spellbinder of death: the resultant of life - the end result of life: the mediator of fate. Tőtszegi is great from the beginning. She pours the royal dust from the urn and plays with it with such naturalness as if she were already engaged to be betrothed to death, but the audience only realizes this after at least two good nights’ sleeps.

Tibor Balogh: Hamlet - Kolozsvár - Gábor Tompa [Hamlet – Cluj – Gábor Tompa], magyarteatrum.hu, January 1, 2022.

In a form of maximum inspiration, Tompa Gábor now creates richly, inventing to saturation situations, new scenic expressions, means, background characters, to support ideas and beliefs that are seething in his soul at such a difficult time for humanity when his conscience gives him the glimmer to express himself and take a firm stand. The target is therefore the landscape of the day. Towards a world and a society hungry for consumption and wealth, globalized but adrift, happy to spread its inventions, not its wealth, around the globe, unconsciously hopping around in artificial paradises (the image is terrifyingly suggested at the beginning of the performance by the loud party at the murderers' wedding) towards the underground foulness that has sickened humanity with scripturism and manipulation, the contempt for culture and the anarchist agitation that fills the squares and stadiums with protests, this major stalemate of the planet with melting glaciers and running out of energy supplies, Tompa Gábor sees in Hamlet not just the rebel on duty, but rather a stoic whose asceticism (he initially appears dressed as a Franciscan monk) does not send him to a monastery, but to a library, among books, even if, as we shall see, culture is no longer useful for restoring the moral order. In one of the most beautiful scenes of the performance, in his cell - a parallelepiped marked with a do not cross banner - which set designer András Both has placed suggestively, somewhere eccentric to the action, the Wittenberg student has a fit of rage, snatching the books from the shelves and throwing them scattered across the stage, where they will lie for the rest of the performance, trampled underfoot.

Doina Papp: Hamlet-ul lui Tompa [Tompa's Hamlet], revista22.ro, January, 11, 2022

A book stall with shutters serves as a refuge for Hamlet when he is in retreat from the world. In the mousetrap scene, the whole court audience surprisingly fits between the shelves, from where they listen to the dialogue read by Gertrude and Claudius, which stops when it is revealed what it is about. This is the most striking scene of the performance. The play in a play scene is not acted out by the traveling theatre troupe suggested by the author. By centering on Hamlet's mother and her uncle/step-father, it provides an excellent opportunity to explore at least three superimposed layers of acting. We see simultaneously the leaders of the Danish royal court, how they move from their status to portray their roles within the play, which is imagined as a social entertainment, and how they regress to their original position, and all the while we see how the actors of the Cluj company accomplish all this. Their bravura is impressive. In contemporary staging, it is very rare to find a situation on stage where the role and the actor find into their place and even enjoy it. Even if only for a few brief moments.

István Sebesi: Szellemjárás Kolozsváron [The Specter Appeared in Cluj], szinhaz.net, January 13, 2022

You can also tell that the world is going is taking a wrong turn by the fact that Gábor Tompa is directing Hamlet. This is the fourth time he has staged the story of the Danish prince, the second time in Cluj-Napoca. The first time was in 1987, the second time in 2021, with the premiere taking place on December 3, and the second performance the next day. One could say that when the times seems to be out of whack, a premiere of Hamlet is happening in Cluj, but most likely in many other cities around the world.

The film-like performance, built as it were in clips, does not paint a very cheerful picture of what we are in, much less of what lies ahead.

Judit Simon: A színház csodája Hamlet kuckójában [The miracle of the theatre in Hamlet's dwelling], ujvarad.ro, 2022. 02. 22.

Gábor Tompa's staging is a tangle of opposites, but the world of the desolate Elsinore is much more complex, mainly thanks to András Visky's dramaturgy, and the stage offers a library of interpretations of Shakespeare's classic, at least much more than the first minutes of the production suggest.

Along this dichotomy, a web of contradictions dominates the performance as a whole, defined by the dialectic of the now and the past: Hamlet is a philosophical old man in a young body, who is much more attached to the values of the past than his hedonistic, throne-stealing uncle. The sword, the automatic rifle, the handwritten letter and the ping of the text message are all simultaneously presented as tools of the leisurely courtiers dressed in contemporary outfits. The Wittenberg group, led by Hamlet and Horatio, the black robes of the opposition may symbolize mourning, but also a kind of monasticism of their own. Claudius's circle is inspired by the upper echelons of authoritarian regimes, here everyone stereotypically has a tattoo and dance to techno music till dawn in honor of the newly wed royal couple;

Emma Rosznáky Varga: Techno-valcer Dániában [Techno-waltz in Denmark], art7.ro, February 10, 2022.

What is Hamlet like in this performance? Is he melancholic? Rebellious? Is he truly mad? What would you say if Hamlet were a distraught young monk figure, who retreats from society like a hermit to carry out his mission in the most precise and dignified way? To do justice, to seek the truth by going within ourselves, by digging into our own inner moral world, through sobering stations of silence, and by digging into the depths of heightened reason to find clarity. Not to live in a false pseudo-truth, glued together with deceit and lust. To live in a morally unworldly reality just because this cataract has infected everyone's eyes? I mean, everyone's cowardly heart and helpless being? Everyone here hides, covers. Except Hamlet, who peels the tissue from cell. The figure of Hamlet sees and acts with his heart, icing, freezing and not clogging the paths of reason.

Patrícia Dimény: Felfokozott felfoghatatlan [The Heightened Incomprehensible], Helikon

The radical figure of Hamlet (played with remarkable precision and nuance between confrontation and abandonment by Miklós Vecsei H.) and his Wittenberg group stands out, revealing a political subtext to the conflict (Balázs Bodolai, Zsolt Gedő, András Buzási, Ferenc Sinkó). On the other side, the character of Gertrude is highlighted, whose inner drift, oscillating between moral cynicism, guilt and maternal instinct is rendered very finely and poignantly by Imola Kézdi; no less, portrayed in firm, bellicose and vindictive tones, is Claudius played by Ervin Szűcs. Interestingly composed is Ophelia's character, whom Zsuzsa Tőtszegi portrays almost seraphically, blurred, somewhat ethereal; picturesque in its attitudinal indecision is József Bíró's Polonius; a specular, vengeful, Hamletian avatar is Tamás Kiss's Laertes.

Claudiu Groza: Între ideologie și parodie (I) [Between ideology and parody (I)], Tribuna, year XXI, 16-28 February 2022

Hamlet is a contemporary retelling of the drama of the Danish prince, with various aesthetic elements (set, costumes) and personal directorial solutions. Miklós Vecsei H. is a charismatic Hamlet, but who is troubled by the revelation of his father's murder. The Prince's madness is presented in a dual way, through the portrayal of madness (with comic tendencies through buffoonery) and the isolationism of the protagonist. Ervin Szűcs as Claudius is a radical counterpoint. Where Hamlet, even in his moments of madness, displays a gallantry, Claudius is a vulgar brute, the image of a fighter highlighted by Bianca Imelda Jeremias' costume, which reveals his massive physical build. András Both's simple scenic construction ramps up the stage and revolves around Hamlet's room (resembling a kiosk) where the action takes place. The setting is completed in the second half of the performance by an enclosed arena (typical of modern contact sports) where the duel between the Prince and Laertes takes place. A particular theme of the performance is that of innocence destroyed by the adult world. The presence of the characters named the child Hamlet and the child Ophelia recalls the innocence of these two characters, subject to madness and death because of the parvenu nature of the society which they are too pure to inhabit. Vasile Șirli's original music complements the stage universe with a simple and suggestive sound structure.

Octavian Szalad: Poezie și muzicală la Cluj: Shakespeare, Ionescu, Cehov, Orwell [Poetry and music in Cluj: Shakespeare, Ionescu, Chekhov, Orwell], Teatru Azi, issues 1-2/2022

The whole performance impresses by the consistency of language, by the particularly fast pace and by the complexity of characters, in the case of Hamlet faithful to the contrariness of human nature. Added to this is the no less significant evolution of the performers, led by Vecsei Miklos in the title role. And as a coincidence worth mentioning, I would refer to Szűcs Ervin's performance in the role of King Claudius, impressive for its inner depth and acting instinct, reminding me pleasantly of Mihai Constantin's memorable creation in the same role in the performance of Hamlet, directed by Tompa Gábor at the National Theatre of Craiova.

Ion Parhon: O lume smintită în oglindă [A foolish world mirrored], Scrisul Românesc, No. 2 (222), February 2022

The modernised performance uses the oldest Hungarian version, János Arany's translation, as a counterpoint, whose elemental poetry and imagery thus generate tension, but also indicate the conservatism - representing tradition, an earlier morality - to which the young people in the play's search for truth hark back. They are, moreover, defined in the play as the Wittenberg Group, indicating that they are educated, worldly-minded young people with strong intellectual ammunition - but one cannot help but notice the reference to the Stalker Group.

Noémi Sümegi: Bőrdzsekis nők nyitottak tüzet, senki sem élte túl [Women in leather jackets opened fire, no one survived], index.hu, 21. April 2022.

A special mention, however, should be made of the Wittenberg Group surrounding Hamlet (the name itself is evocative, suggesting timeless parallels), the next-generation, whose members we sense want something different from what is. This is one of the most important building blocks of the direction, that while the protagonist remains a central figure in his struggles, the group (i.e. the community) provides a strong counterpoint to the King's circle that is driven solely by power and interest.

Judit Ungvári: Közösségépítés egy perverz világban [Community building in a perverse world], mitem.hu, 21. April 2022.

Hamlet is a mirror, every age, every generation can look at themselves in it. In war, in peace, in dictatorship, in emotional slumps and mountainous peaks of passion.

Tompa's Hamlet is a complex world. A harmony of disparate elements woven into an organic whole; the interplay of generations as everything and everyone is homogenised by an increasingly violent and brutal outside world.

What is most striking in the performance, beyond the cascade of images and the musical composition, is the text, the text of János Arany. The director's choice is striking and reveals the "world view" of the performance. The production confirms the choice of text to the fullest, there is no archaic flavour, the sentences roll effortlessly off the lips of the characters, and the phrases that have long since become a catchphrase can be uttered, "time is out of joint", "frailty, thy name is woman”, etc. The creators, dramaturg András Visky, director Gábor Tompa and their colleagues, have enriched Arany's not ageing, but nobly patinated, yet pathos-free text with sparingly added texts.

Dezső Kovács: A fiú, az apa és a kizökkent idő [The Son, the Father, and the Out of Joint Time], art7, 29. April 2022.

It is Tompa's brilliant idea that the so-called mousetrap scene, in which actors originally act out how the current king has poisoned his predecessor, is not accompanied by any drop-kickers. Hamlet, with clever wiles, also invites Claudius to play a part in the evening's play, but he only presses the text, adapted for the purpose, into his hands on the spot. It is only when he says he is playing his part that he realises he is making his own sin public. Ervin Szűcs shows that he is totally upset: his anger is terrible, but later he prays, trembling.

Gábor Bóta: Apokaliptikus vízió [Apocalyptic Vision], 01. May 2022.

The company of the Hungarian Theatre of Cluj, director Gábor Tompa and the entire creative team set the right cadence, found and explored the accurate interpretative nuances. Hamlet challenges us to take a look at our world, even if the lens used as a pretext seems to point to another time. What's more, it invites scrutiny of concepts that we too often think of today as having already been clarified and, above all, classified: truth, loyalty, betrayal, usurpation, power - to name but a few.

Daniela Șilindean: Showcase Hungarian Theatre of Cluj (I), Orizont, 2022 No. 2 (1678), Year XXXIV

I could see William Shakespeare's Hamlet, directed by Gábor Tompa, at least three times (I've already seen it twice) - for several reasons. The play's central prince is, ideologically speaking, the son with two fathers: one is the rightful king and Hyperion turned spectre and guiding magister (in the play's eschatological logic), the other is Yorick, the jester who was the spiritual guardian of the child who should have become king, even if Yorick is only symbolically present through a skull. These two directions in the formation of Hamlet are skillfully staged by Gábor Tompa and are part of the spectral ideational charge of the Shakespearean text speculated by the Hungarian director.

Ruxandra Cesereanu: Hamlet triform: prinț, călugăr, bufon [Threefold Hamlet: Prince, Monk, Jester], Teatrul Azi, Issues 5-6/2022

This time Hamlet is no longer alone, he is surrounded by a group of young people, or the Wittenberg Group, the university where the young prince was educated. A few other bold suggestions, Ophelia is no longer crazy, her monologue is very clear, resounding, she is perhaps the only one who understands what is going on. The gravediggers' scene is simplified, we witness a television interview, but most importantly, the scene depicting a play within a play is staged by Hamlet, the director manipulating the characters - here Claudius and Gertrude. A recurring motif in Tompa's directorial imagery is that of the library, a kiosk where Hamlet retreats among the books he will destroy at the end... If there are some simplifications and cuts, at the end we hear an excerpt from a speech given by Nehru on Gandhi's death, a kind of appeal for general appeasement. Notable are two children, somewhere in the back, watching everything, like visitors from the past. A very young Hamlet, Miklós Vecsei, from Budapest, who naturally carries the themes and despair of our time, and Ervin Szűcs, a powerful yet different king. His prayer, which Hamlet secretly captures, is in fact the desperate, impossible prayer of an atheist, praying to a hollow sky...

Mirella Patureau: Between fear and hope, in Cluj, theatre has definitely chosen hope, Observator Cultural, no. 1138 (878), December 7-17, 2022